Prior to World War II, Heywood-Wakefield was a primary producer of rattan furniture. During the War, their rattan operations came to an abrupt halt as global trade routes collapsed. Most commercial rattan had been imported from Indonesia, which fell under Japanese occupation, cutting off supplies of cane, reed, and rattan almost overnight. Factories that once turned out wicker and reed furniture were quickly retooled to produce military goods instead.

By late 1945, as wartime restrictions lifted, Heywood-Wakefield returned to civilian manufacturing, modernizing its equipment and design language to meet the needs of a booming postwar housing market. Although rattan imports eventually resumed, they did so slowly and at much higher cost, making large-scale American production impractical.

Meanwhile, demand for rattan soared on the West Coast and in the Sun Belt, especially in California, Florida, and Hawaii. A new wave of tropical leisure culture swept through American design, inspired in part by returning servicemen who had served in the Pacific and brought home an appetite for island imagery in the form of bamboo, rattan, surf, tiki bars, and lanai furniture.

Even as genuine rattan became scarce, its look – light, relaxed, and suggestive of vacation living – captured the American imagination. For millions of GIs and their families moving into new suburban homes, rattan-style furniture symbolized modern comfort and optimism. Sun porches, patios, and Florida rooms became showcases of postwar prosperity, filled with the easy warmth of a material that had come to represent relaxed, modern living.

Heywood-Wakefield’s once-thriving New England rattan manufacturing base had all but disappeared. The old Wakefield Rattan Company and Heywood-Wakefield reed workshops had either burned, closed, or been retooled for wartime production. Skilled cane workers, many of them immigrants who had mastered the art of hand-weaving, had moved on to other trades, and the specialized machinery once used for shaping and weaving rattan had been replaced by woodworking lines turning out bent birch and ash. When the war ended and rattan imports from Southeast Asia resumed, the infrastructure, labor, and expertise that had once supported East Coast production were gone, leaving no established manufacturing ecosystem ready to take advantage of the renewed supply.

Meanwhile, rattan imports resumed through new trading routes in the Philippines, where abundant raw material and inexpensive labor allowed large-scale handcrafting again. A new generation of West Coast companies like Paul Frankl, Ficks Reed (Cincinnati but marketed nationally), McGuire (San Francisco), Tropitan (Ritts Company of Los Angeles), and others entered the market.

Postwar rattan furniture emphasized streamlined loops, bold curves, and minimalist joints—a tropical echo of modernism. Frankl’s “Pretzel” chair, with its continuous bent rattan arms, became an icon. Ritts’ Tropitan line blended bamboo, rattan, and plywood with vibrant island upholstery, and Florida makers like Braxton Culler and Henry Link turned out “lanai” suites that defined the new American casual interior. While rattan was being reborn on the coasts, Heywood-Wakefield faced a supply and labor crisis. The company was also repositioning itself as a modern manufacturer of blonde birch furniture for middle-class homes.

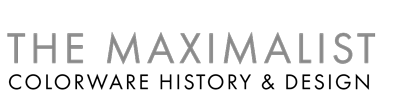

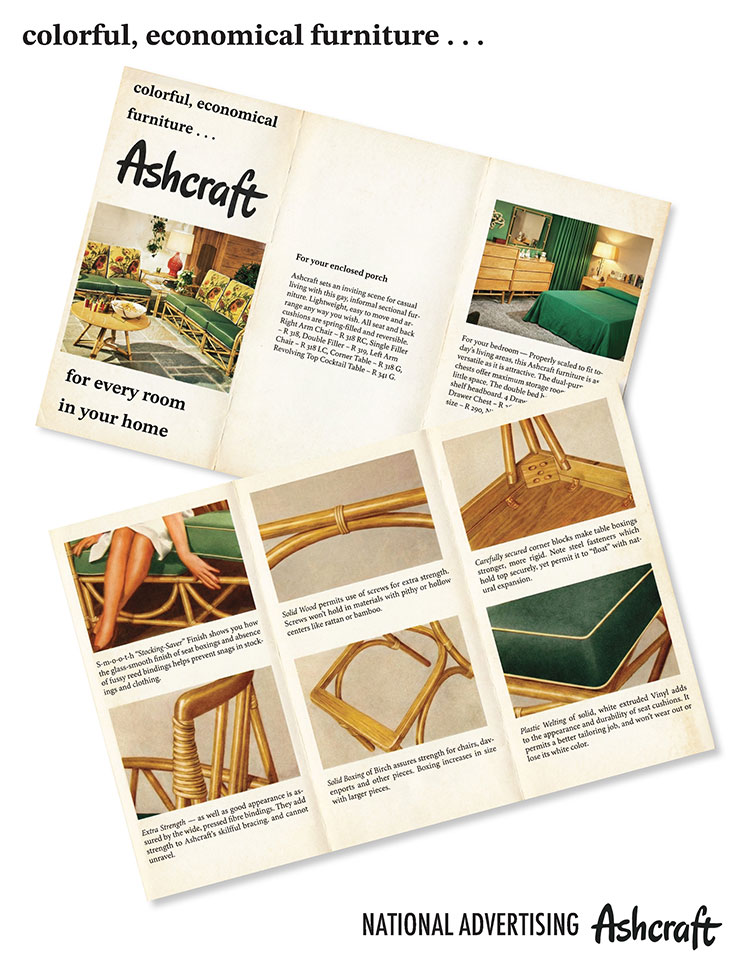

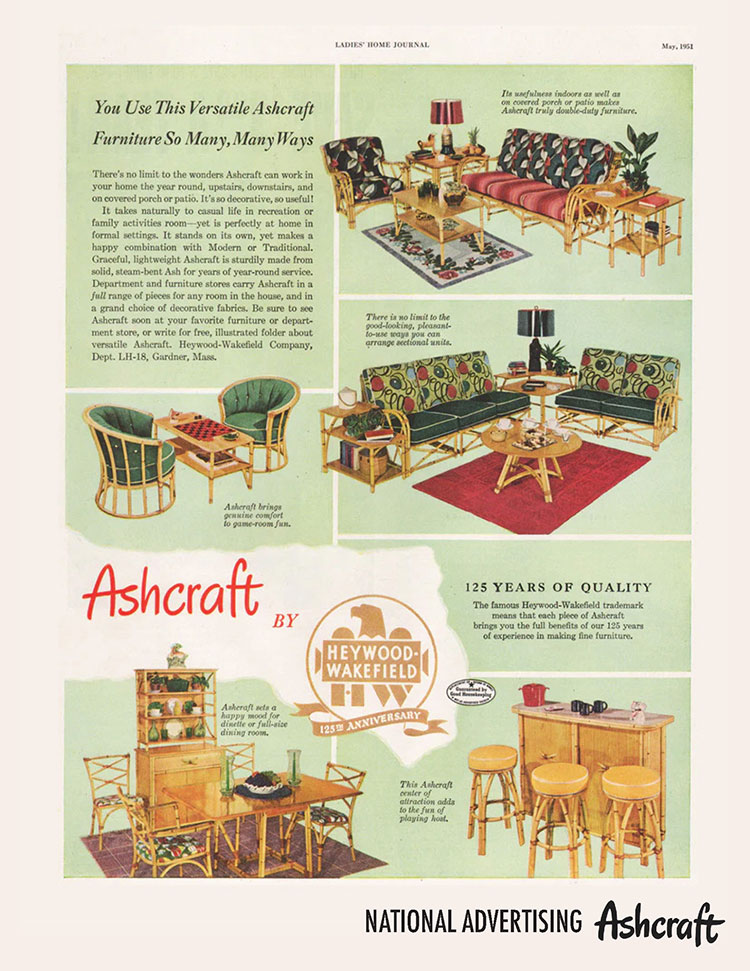

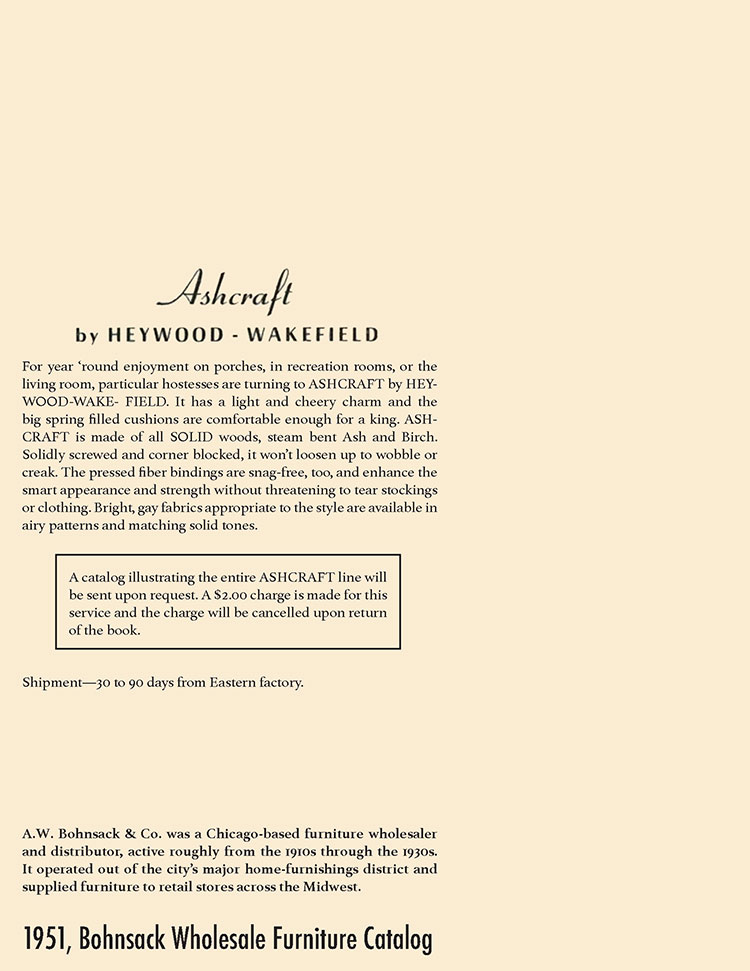

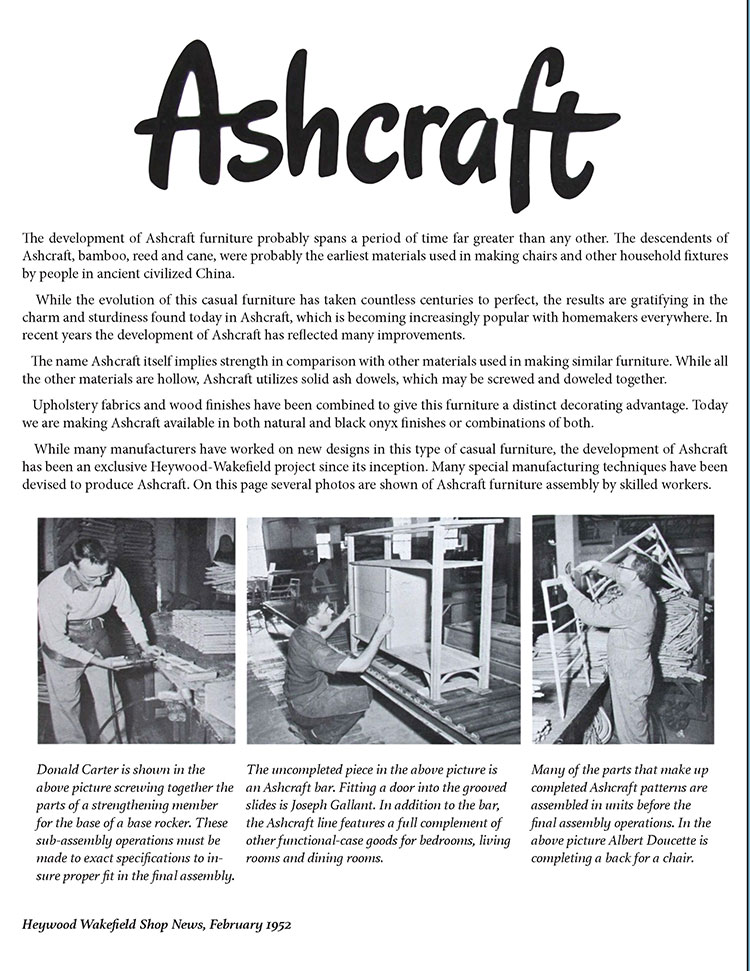

Instead of competing with tropical imports, Heywood-Wakefield’s answer was ingenious: replicate the airy, relaxed appearance of rattan using domestic hardwood and modern production methods. Heywood engineers created Ashcraft: a domestic hardwood interpretation of rattan’s airy forms. It kept the visual language—curved frames, wrapped joints, sunroom silhouettes—but substituted ash bentwood for cane, raffia for binding, and a wheat-toned finish for the honey glow of natural rattan.

Ashcraft also harmonized with the evolving taste of the late 1940s–50s. While the coastal rattan movement leaned toward tropical fantasy and Tiki exuberance, Ashcraft appealed to the restrained modernism of the early postwar home: modest ranch houses, sunrooms, screened porches.

Its bent-wood forms and clean lines blended with Heywood-Wakefield’s emerging blonde birch modernist furniture, giving consumers continuity between their “indoor” and “outdoor” styles. It was tropical enough to feel new, but polished enough to feel respectable.

Heywood-Wakefield produced Ashcraft from around the late 1940s to the late-1950s and was phased out as American tastes and materials evolved. Enthusiasm for breezy “Florida room” or “lanai” furniture gave way to the sleek, low-profile lines of modern living-room suites. Heywood-Wakefield’s Modern furniture became far more popular and profitable.

Additionally, imported rattan furniture from California and the Philippines became inexpensive and widely available again, undercutting Ashcraft’s appeal as a substitute. Retailers could now sell genuine rattan at competitive prices, while Heywood’s hardwood imitation cost more to produce. The line no longer fit either the company’s production model or the prevailing design taste of the time. It was a beautiful but transitional idea, a bridge between the rattan revival of the 1940s and the pure modernism that came to define mid-century American furniture.